How to learn words

Why are there four forms on every picture?

tl;dr: you need to learn four base forms for each word to be able to use it correctly in every context and derive other forms

What makes learning frustrating

One of the things I find really frustrating when learning anything is finding out halfway through the process that there is a thing you should have known about.

And then you need to go back and revisit all of the material you already know.

Or quit.

I’ve quit many things like this, but a few times I persisted and worked through the material again.

Languages are no different in that regard.

Words change their shape

Words change based on their function in the sentence or the meaning you want to convey.

Consider the verb (“action word”) “to do” in English:

are all “forms” of the same word – the basic idea is the same, but the meaning conveyed differs in each instance.

Why do you need to learn all of these forms, for every verb in English?

Because you cannot derive all forms from one.

Actually, that’s inaccurate. For many verbs, you can derive them.

According to rules.

We call these regular verbs because they follow rules, and the other verbs irregular, because they don’t.

Once you know the rule, you can apply the rule and get a correct result.

In the case of English, there are about 200 irregular verbs according to Wikipedia, for which no rules apply and we just need to learn them.

Estonian words

We can group words into different categories based on how they change and what they express.

Most, if not all languages at least distinguish between two kinds of words:

nounsare “thing words”: they name concrete or abstract things. Examples: apple, tree, noun, word, thingverbsare “action words”: they express an action or activity somebody or something is performing. Examples: to do, to eat, to drink, to think.

Estonian also has these two groups.

For words in each group, you need to learn 4 base forms.

Once you know these 4 base forms, you can derive all other forms with a high degree of accuracy.

If you don’t know the base forms, you’ll struggle with building basic, correct sentences.

You do not need to worry about what these base forms mean for now.

Just accept that you need to learn them to help your brain figure out patterns.

If you don’t want to do that, accept that you will be puzzled.

Verbs

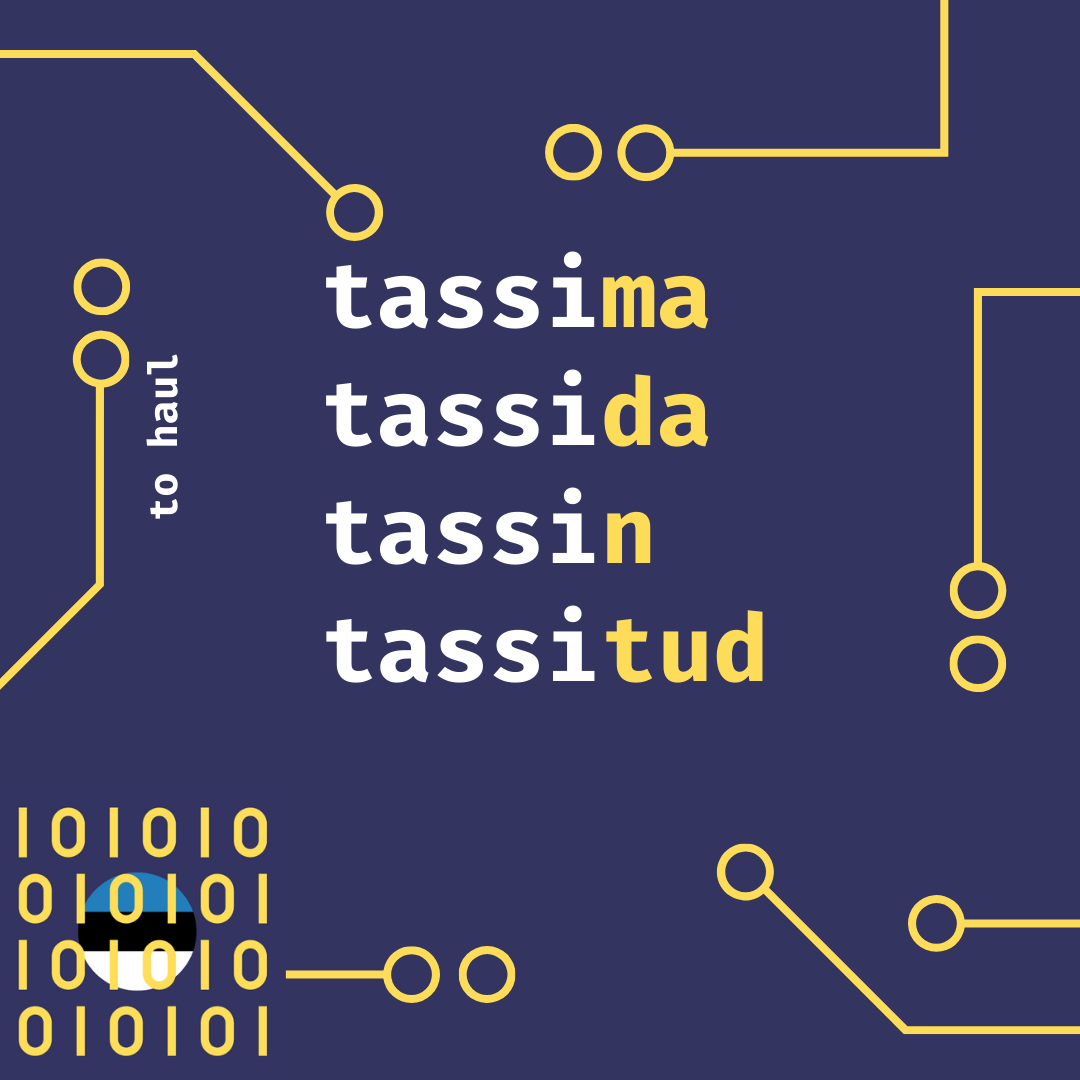

These are the four base forms commonly listed in proper Estonian dictionaries:

the “

ma Infinitive”, essentially like “to haul” in English. It’s called that because it ends withma.the “

da Infinitive”, also like “to haul” in English. It mostly ends withda, and there is a logic behind the instances where it has a different ending.the “first person singular present indicative” or the “I am doing” form. So “tassin” means “I haul”.

the “past participle passive” or the “

tud Participle” corresponds to the past participle in English, e.g. “tassitud” means “hauled”.

This is not the full truth, but only the useful part of the truth with the minimal amount of acceptable confusion right now.

Nouns

For nouns, the story is similar:

Nouns in Estonian don’t change in order to indicate when the action is taking place or how the action is performed.

Instead, they change their form to indicate their role in the sentence, i.e. to mark who is performing the action or to whom the action is done.

For nouns, we call these different forms cases.

The base forms are, in order:

The Nominative Singular: indicates “who” is doing the action in the sentence.

The Genitive Singular: indicates “whose” something is, e.g. “

toa uks” is “the room’s door”. Besides that, it is also the basic building block for many of the possible derivations.The Partitive Singular: indicates the target of the action, i.e. “to whom something is done”. It also has a lot of other functions, which we won’t cover here.

The Partitive Plural: same as the singular, but for many instances of the thing.

Dangerous half-truths

All of the information presented above is targeted at getting you to understand, identify and use words correctly at least 80% of the time, with 20% of the confusion necessary to understand things.

That being said, when you read “always” here, it actually means “most of the time”.

Rules presented here apply most of the time, not 100% of the time unless stated otherwise.

If you feel cheated now, I understand.

However, this approach works really well with your brain.

In order to deal with the irregular, your brain first needs an idea of what the regular is.

You know, “no shadow without a light” and such.

And since there is a potentially very large amount of irregularities to learn, we are not going to focus on those, because that’s demotivating and delaying progress.

We focus on the regularities so that you are able to figure out the irregularities on your own.